The Ethiopian government released earlier this week its preliminary report to the public for the March 10, 2019 accident involving Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. The report included plots of the Flight Data Recorder data and a detailed time history of events including those derived from the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR). Review of these data show the MCAS automatic stabilizer trim activations occurred between 250 and 340 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS), which is on the upper end of the 737’s operating speed range. The data also show the pilots tried but were not able to use manual stabilizer trim to remove the nose-down trim established by the MCAS, even when the CUTOUT switches were activated per Boeing’s post-Lion Air emergency procedures.

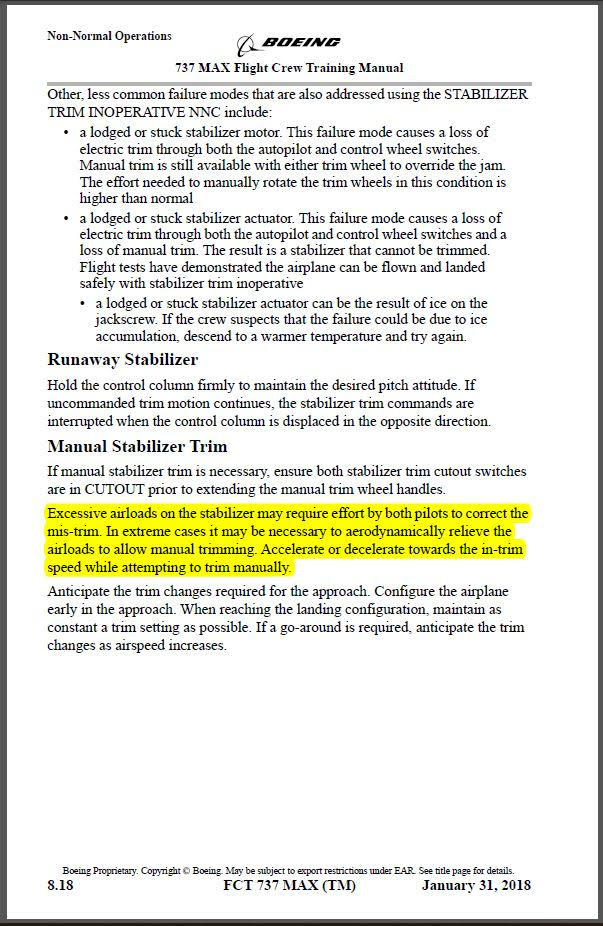

Page 8.18 of Boeing’s 737 MAX Flight Crew Training Manual likely explains why the Ethiopian flight crew was unable to retrim their airplane and prevent the accident, as highlighted below:

What Boeing and the FAA didn’t tell the world after the Lion Air accident is that their 737 manual stabilizer trim system only works with typical human strength inputs at lower airspeeds, and that at high airspeeds such as occurred with Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, pilots might not be strong enough to correct the problem with manual trim inputs. They should slow down via reducing their engine power until the air loads on the stabilizer decrease enough to allow the pilots to move the manual trim wheels.

This faulty training manual also falsely states that uncommanded trim motion will be interrupted when the control column is moved in the opposite direction by the pilots. That is true for a normal runaway stabilizer motor failure but not true for an MCAS-commanded stabilizer movement, and thus pilots were falsely led to believe that merely applying control column force would stop any form of stabilizer trim movement that they didn’t want. This had to be very confusing for the Lion Air and Ethiopian flight crews that their 737 stab trim training was not working, and it was all because Boeing didn’t want them to know about MCAS because then they would have required expensive retraining on how MCAS works and affects the control of their airplane.

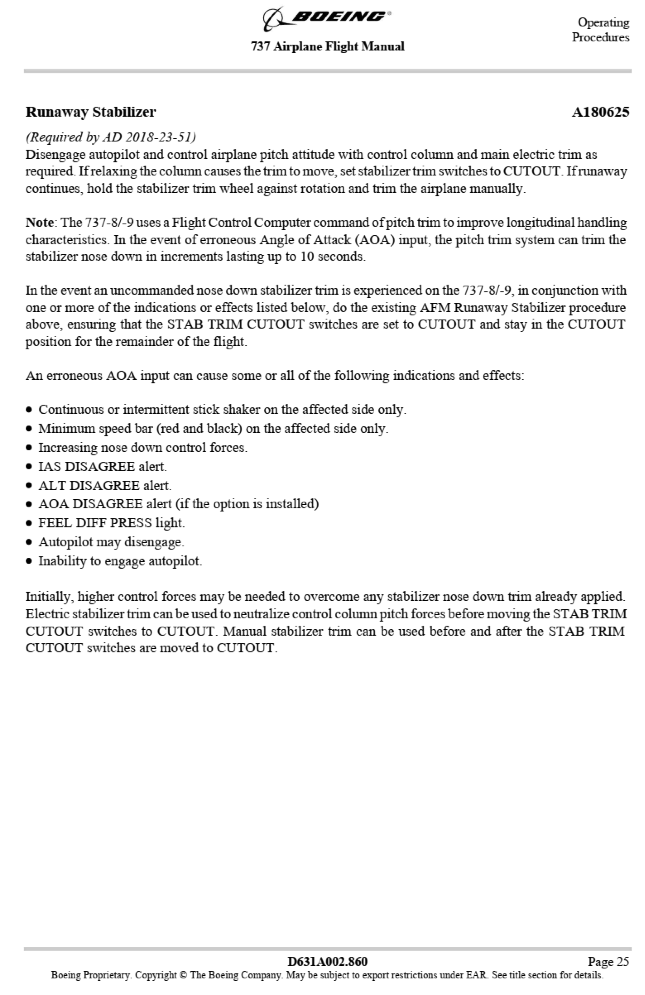

As with the 737 MAX design and certification, neither Boeing nor the FAA did their jobs thoroughly or safely after the Lion Air accident and they rushed to show that the accident was all pilot error in their minds and had little to do with their design and certification efforts. Consequently, after the Lion Air accident, Boeing and the FAA put the following out as their guidance on how to prevent recurrence:

Notice Boeing and the FAA failed to mention anything about high airspeed possibly preventing pilots from being able to manually trim or, even better, that they should slow the airplane until trim forces are manageable and safe, even down to the minimum maneuvering speed for their configuration. The Boeing training manual makes it clear, Boeing knew pilots needed some awareness that manual trim might not work at high airspeeds, but they failed to transfer that critical knowledge to their operators and pilots in their post-Lion Air guidance. A proper system safety study and accident investigation effort would have yielded these pilot education and training requirements, and likely prevented the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. This is yet further evidence of Boeing and the FAA lacking attention to detail and safety that is expected of airliner manufacturers and regulators.

Is it safe to allow the 737 to operate with a manual backup trim system that will only work in the lower airspeed range of its envelope, especially when pilots aren’t properly educated and trained in its limitations and how to get around those limitations? Is it safe for training and flight manuals, as well as simulator training programs, to exclude information on background automatic flight control systems like MCAS? Is it safe to allow a stall warning system (the stick shaker) to activate falsely due to a single angle of attack (AOA) sensor input, thereby leading flight crews to believe their airspeed may be too low, yet increasing their airspeed may cause them to lose control of the manual stabilizer trim that they need to save their lives from a false MCAS activation?

Boeing and the FAA, as well as international airworthiness authorities and airline operators, should each do a thorough analysis of these two 737 MAX accidents and the airplane’s design, maintenance, continuing airworthiness, and training programs, to identify and require all safety improvements that will prevent recurrence of this MCAS accident scenario. Human factors design must be especially thorough now that we have pilots from all corners of the world, of all age groups, and of all possible spectra of education and training operating airliners such as the 737 MAX. Boeing and the FAA failed miserably in their jobs at doing so thus far for the 737 MAX – this may be their last shot at redemption.